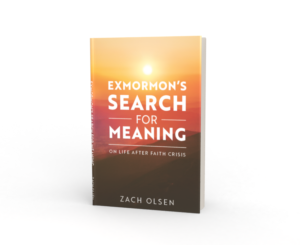

During her time as a palliative carer, Bronnie Ware identified what she called the top regrets of dying, which are:

- “I wish I’d had the courage to live a life true to myself, not the life others expected of me.”

- “I wish I hadn’t worked so hard.”

- “I wish I’d had the courage to express my feelings.”

- “I wish I had stayed in touch with my friends.”

- “I wish that I had let myself be happier.”

In a Ted Talk describing these regrets she says, “Time is a gift. How we choose to use that gift will determine whether we are creating a life of regret or a life of joy, and the choice is ours.” She further states that all of these regrets stem from an individual’s “lack of courage.” For those who want to die regret free, her advice is individual accountability. If one dies with regret, that is one’s own fault.

I think this is the wrong approach.

While we should try to be as purposeful with our lives as we can be, it is not our choices that will save us from regret, but the stories we invent to describe those choices that will make the difference. What makes a decision noble or an experience fulfilling or an event memorable is up for interpretation. Individuals, and more importantly the cultures in which those individuals reside, are what’s responsible for those interpretations. An increase in people dying with regret should be looked at as a failure of creating meaning rather than a failure of individual achievement.

The ability to decode choices and experiences and place them in the most fulfilling narrative as possible is a skill one must learn. Before learning this skill, we’re subjected to using the narrative we inherit from our culture, and our American culture does not provide realistically attainable values conducive to dying without regret, placing an even higher priority on the skill of meaning-making.

In American culture, success–one of the utmost prized American values–lies squarely on the individual’s shoulders. Meritocracy turns failure from a misfortune to an unquestioning verdict of one’s moral fiber. It’s “fair,” after all, that people get what they “deserve”. So, those who are unhappy must have been lazy or did something wrong; those who are happy must have worked hard and were good. Within this construct one may still be able to derive success on their own terms–individualism being a beneficial American value in this case–but it is an uphill battle against the inexorable drumbeat of America’s version of success which beats into the heads of its citizens that unlimited wealth and infinite physical beauty, both of which are decidedly impossible to acquire, are the foremost measures. “Live without regrets,” is just one more unobtainable value piled on top of the already anxiety-inducing list.

Rather than encouraging people to “live without regret” based on criteria wholly outside of their control, we should encourage people to incorporate whatever experiences they have had into the most fulfilling narrative possible. This is not unlike the Philosophy of Stoicism’s observation that if you expect the universe to deliver what you want, you are going to be disappointed, but if you embrace whatever the universe gives, then life will be a whole lot more fulfilling.

Rather than allow our culture to decide if our life choices warrant regret by asking, What do I need to do to live without regret; instead ask the question Ernest Becker asked in The Denial of Death: “What is the best illusion under which to live? Or what is the most legitimate foolishness?…the whole question would be answered in terms of how much freedom, dignity and hope a given illusion provides.”

Bronnie Ware said that time was a gift. I agree, however, it’s our ability to create meaning that is the ultimate gift. It is that gift, not time, that will determine whether we are creating a life of regret or a life of joy, and that choice is truly ours.