I saw the Mr. Rogers documentary , “Won’t You Be My Neighbor?” and something Rogers said struck me.

“What we see and hear on the screen is part of who we become.”

I completely agree. The information we consume affects us. It seems like a pretty believable statement but you wouldn’t think so considering how unthinkingly we consume information.

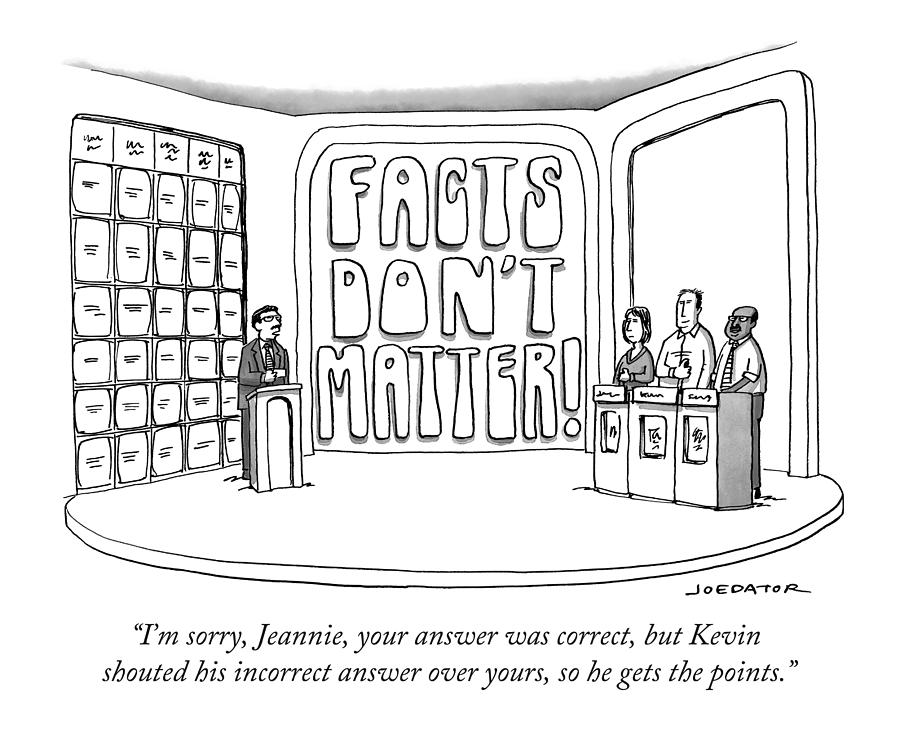

Consider the story with Facebook where user data was taken by Cambridge Analytica to use for political campaigning. People were outraged that data was taken from them without their knowing to serve them content that they didn’t want. Yet, nothing happened. Reports say Facebook usage actually increased.

A person walking out of a Whole Foods could be accused of being a fool for over paying for their natural, organic, fair-trade groceries instead of getting them from a typical store down the street. But the purchaser responds, “What price do you put on your health?” Whether or not that high-priced food is actually healthier is another debate. The laudable thing that Whole Foods customer is trying to do is be conscious and deliberate in their food consumption. When it comes to information consumption, the question not enough of us are asking is, “What price do you put on your thoughts?”

Every thought in your head is sourced from where you place your attention. The fear, outrage, disgust and contempt buzzing in our heads is directly proportional to the information we consume that gives those emotions a chance to grow. We seem to accept that the awfulness of the media is some natural outgrowth of the world we live in. In fact, it’s a reaction to the 24 hour news-cycle where leeching more and more of our attention became a business goal. There’s always front page news because there’s always a front page — not because the news on that front page is actually newsworthy. Feeling fear, outrage, disgust and contempt on a regular basis is an option — one you don’t have to choose if you don’t want to.

We are much further along in recognizing the effects of diet on physical health than we are in recognizing the effects of information on our mental health. Consider the amount of interventions and innovations that exist today to help us eat healthy: nutrition labels, calorie amounts on menus, diet books, personal trainers, nutritionists. Now compare all that to the lack of interventions devoted to improving our consumption of information. There are some ‘hacks’ to help curb smartphone addiction and some books on the topic, that’s about it.

The information that affects us is not limited to news. We also need to be concerned with tv shows, movies, youtube, comic books, Instagram feeds, billboards, music, product packaging, etc. This makes the challenge very complex. Continuing the analogy of information consumption compared to food consumption helps.

A calorie can be thought of as a unit of energy – if the amount of energy we consume is greater than the amount of energy we spend, the excess is stored in fat. This sounds simple but a calorie for one person is not the same as a calorie for another. Every individual’s ability to extract energy from food is a little different. So a calorie is a useful energy metric, but to work out exactly how many of them each of us requires we need to factor in things like exercise, food type, and our body’s ability to process energy — it’s not easy.

The same goes for trying to understand a unit of measurement for information consumed. The best tool we’ve got is listening to ourselves. We need to pause and reflect on the information we consume and pay attention to how it makes us feel.

Penn Jillette says food consumption is driven more by habit than by taste:

“It turns out everything about eating is habit. It’s all habitual. You think you have a natural inclination to like grilled cheese or donuts. Not true. All we eat is habit.”

I’m convinced that almost all content is consumed out of habit too making us feel just as lethargic as eating a bag of chips. Most of the information we consume is not even enjoyed. Consider Aziz Ansari’s test:

“Take, your nightly or morning browse of the Internet, right? Your Facebook feed, Instagram feed, Twitter, whatever. If someone every morning said, “I’m gonna print this and give you a bound copy of all this stuff you read so you don’t have to use the Internet. You can just get a bound copy of it.” Would you read that book? No! You’d be like, this book sucks. There’s a link to some article about a horse that found its owner somehow. It’s not that interesting.”

It took the obesity crisis to draw awareness to the food we eat. Let’s not wait for a crisis in mental health to draw attention to how powerful the information we consume affects our well being.

Be aware of how your attention is hijacked. Consume content on your terms, not on the phone’s. Letting Facebook decide what’s good for you to read and watch would be like letting McDonalds choose what you should eat.

To only seek information and entertainment that makes us feel good would be doing ourselves a disservice. Don’t binge on empty information calories. Broccoli needs to be consumed just as much as the salty and sweet snacks.

Remember the complexity of every issue. Attack the deep details of subjects to see the multiple facets being explored, the reasoning used by the other side and ask child-like simple questions that’ll lay bare the incredible complexity of everything.

Consider Bill Watterson’s idea, creator of Calvin and Hobbes:

“We’re not really taught how to recreate constructively. We need to do more than find diversions; we need to restore and expand ourselves. Our idea of relaxing is all too often to plop down in front of the television set and let its pandering idiocy liquefy our brains. Shutting off the thought process is not rejuvenating; the mind is like a car battery-it recharges by running.”